John Coppin: A Study in Portraiture

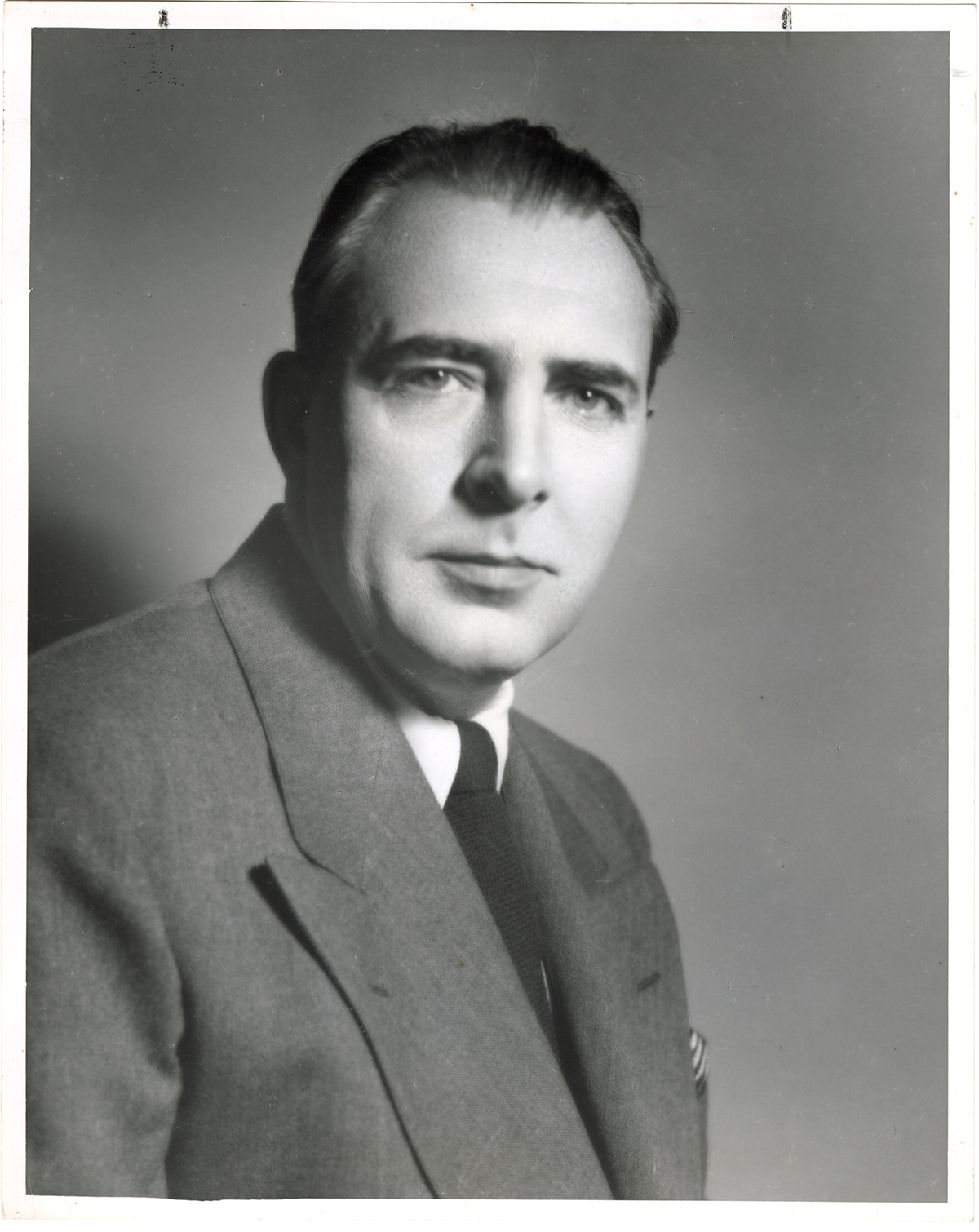

1904 - 1986

The Michigan State Capitol is home to a remarkable collection of gubernatorial portraits, including four painted by artist John Coppin (1904–1986). This virtual exhibition takes a closer look at Coppin’s work, highlighting how his relationships with his sitters shaped the outcome of each portrait.

As you explore, you will see how Coppin’s attention to lifelike detail, personality, and pose created portraits that go beyond likeness to capture the character of Michigan’s governors.

Coppin and His Sitters

An artist’s relationship with their sitter can have a profound impact on the outcome of a portrait. While these dynamics are not always immediately visible in a piece, there are some instances in which it is quite apparent.

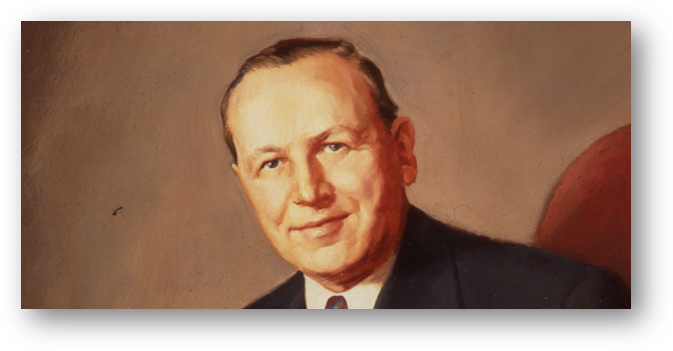

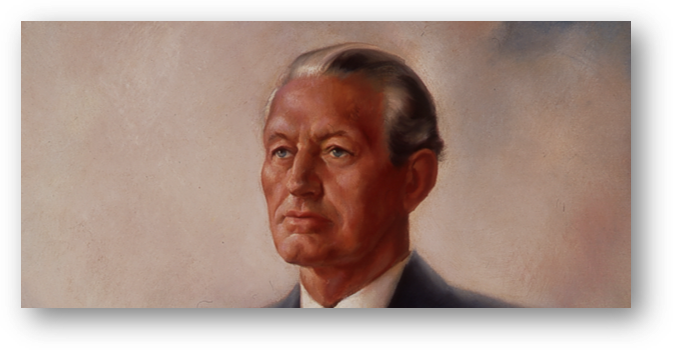

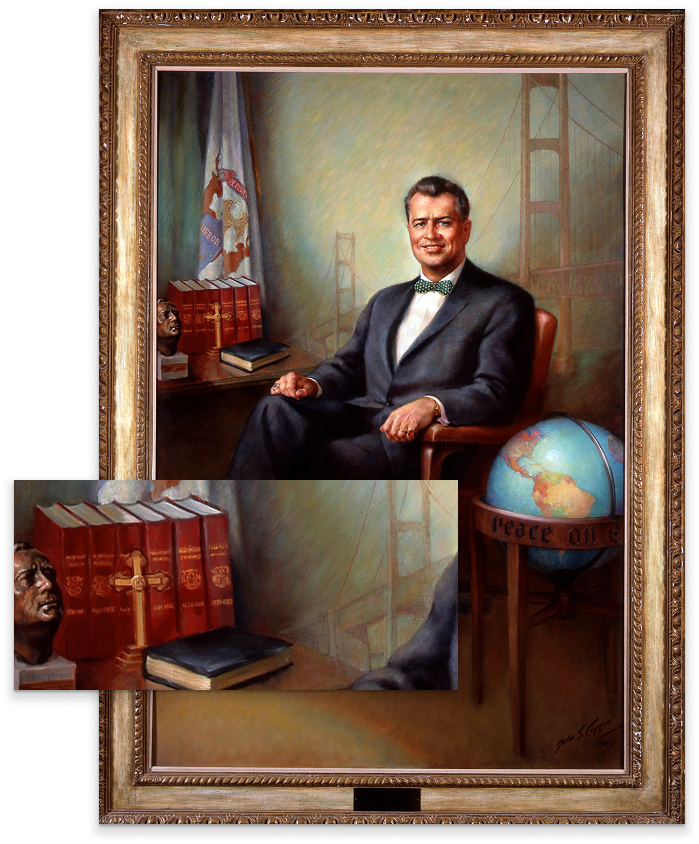

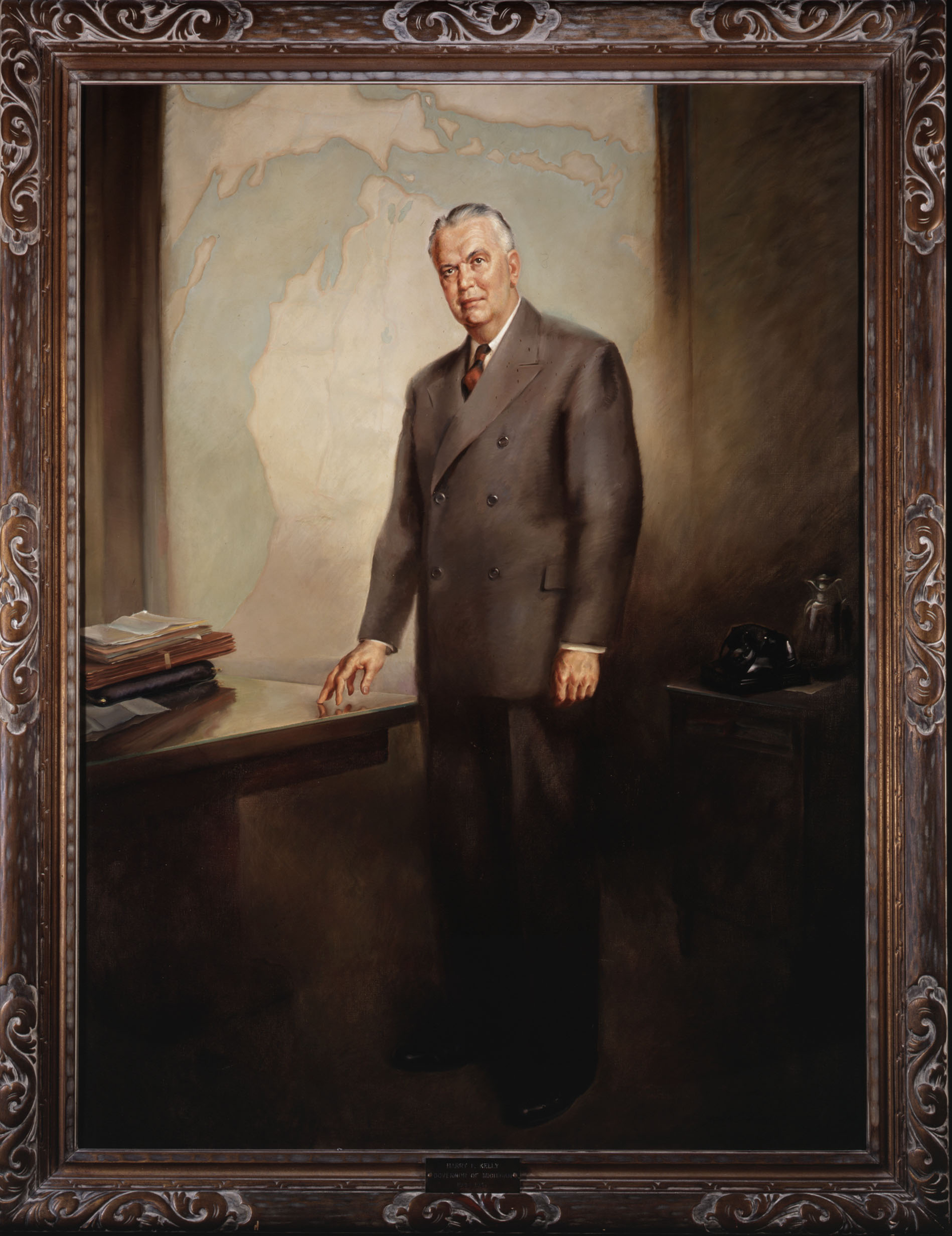

The four portraits by John Coppin (1904-1986) in the Capitol’s collection serve as an excellent example of this phenomenon. Coppin completed his first painting for the state in 1944, when he painted Governor Murray D. Van Wagoner. He went on to complete portraits of the subsequent three governors: Harry Kelly, Kim Sigler, and G. Mennen Williams.

Paramount

Precision

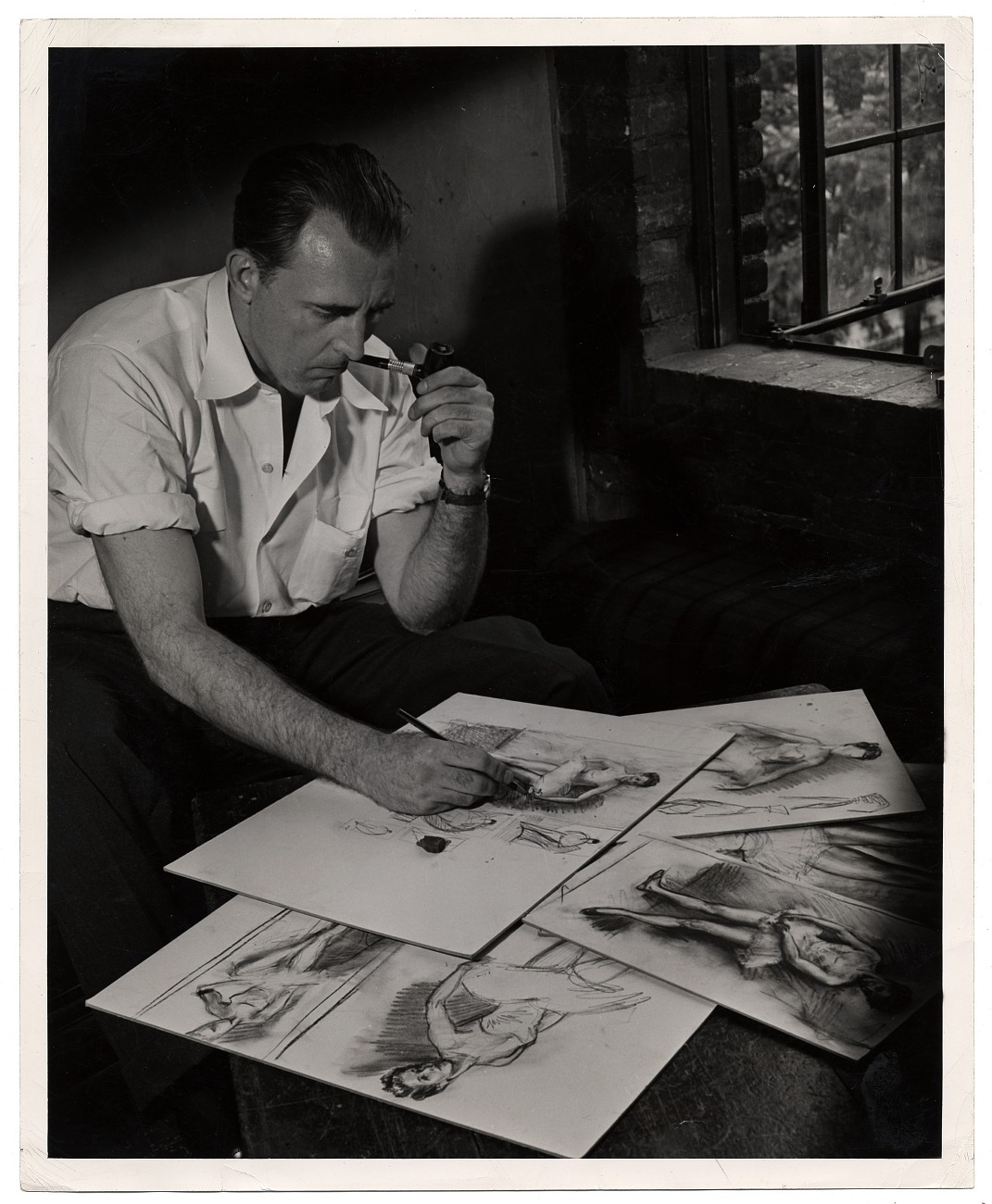

Coppin’s portrait style is consistently naturalistic, meaning that he paints his subjects in a lifelike manner. In 1983, a reporter from the Sarasota Herald Tribune wrote, “Coppin’s paintings are so true to flesh tones that a critic noted that if you cut them they’d bleed.” The artist considered achieving a believable and accurate flesh tone “of paramount importance” in a painting.

Expression at the Heart of Portraiture

Coppin was not satisfied with solely capturing an accurate physical likeness, however. Instead, he sought to holistically portray his subjects, stating, “A portrait is a work of art representing an individual. The pleasure derived from looking at it is due to its value as a likeness, as well as its aesthetic qualities. It should awaken in the beholder the feeling that he is looking at the personal, physical, mental, and characteristic qualities of the portrayed subject.”

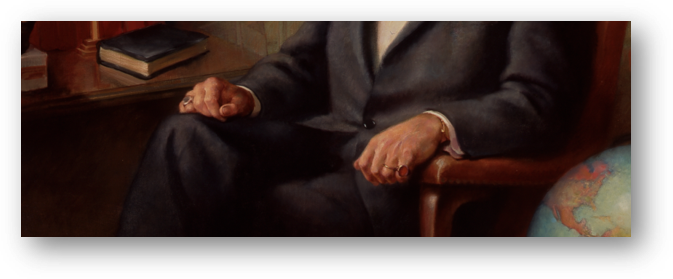

Along with the coloring of the skin, therefore, Coppin also placed emphasis on properly capturing a person’s expressions. This can be seen, in particular, in the way he paints the faces and hands of his sitters. In interviews, he often discussed his search to uncover the true personality of each of his subjects through close observation. He once stated, “As the person is, it begins to show on the outside. The eyes, of course, are the real key. They reveal the mind. The eyes and hands give a person away. What a person does with his hands gives an indication of what he thinks, more than does a face that can be controlled.”

“A portrait is a work of art representing an individual. The pleasure derived from looking at it is due to its value as a likeness, as well as its aesthetic qualities. It should awaken in the beholder the feeling that he is looking at the personal, physical, mental, and characteristic qualities of the portrayed subject.”

Personalized through Collaboration

Outside of these key areas on his figures, Coppin became a bit more creative. Clothing and background elements, for example, might be more colorful, detailed, or unique. He relied on the preferences and expectations of his sitters to determine how traditional or imaginative he could make each portrait. This resulted in outcomes that, at first glance, might not look as if they were all made by the same hand. Coppin’s willingness to collaborate with his sitters in order to best capture their personalities – even when this meant straying from the “norm” – makes his body of work in the Capitol’s collection an intriguing and worthwhile case study.

Governor Van Wagoner

Governor Kelly

Governor Sigler

Governor Williams

“The less flexible, the less exaggerated a person’s expression, the easier he or she is to paint [… ] when the mouth is open, as in talking, the eyes are less open. The minute one smiles, the eyes close a little. There is a degree of distortion from the norm.”

Conversations Between Coppin and Sitter

Coppin’s approach to portrait sittings centered around making his sitter feel comfortable. He would start conversations about topics that interested them, from clothes and books to philosophy. In a conversation about his sittings, he once noted, “It is an emotional experience on the part of both. It takes two to make a portrait. I must have the sitter with face relaxed, and mentally interested; mentally alive, relaxed and happy. I want the sitter first of all to get comfortable in the chair. Then the conversation and music to help put the sitter at ease.” By taking his subjects’ mental state and comfort into consideration, Coppin created a space for them to speak, move, and sit naturally. This helped reveal the “neutral” expressions he sought to depict, ultimately making his portraits appear as more accurate likenesses of the individuals he painted. The four Coppin portraits that hang in the Capitol today serve as a testament to the success of Coppin’s approach and the importance of healthy rapport between artist and sitter.

Explore the Collection For Yourself

Explore the Capitol’s ornate interior and observe our portraits in person.